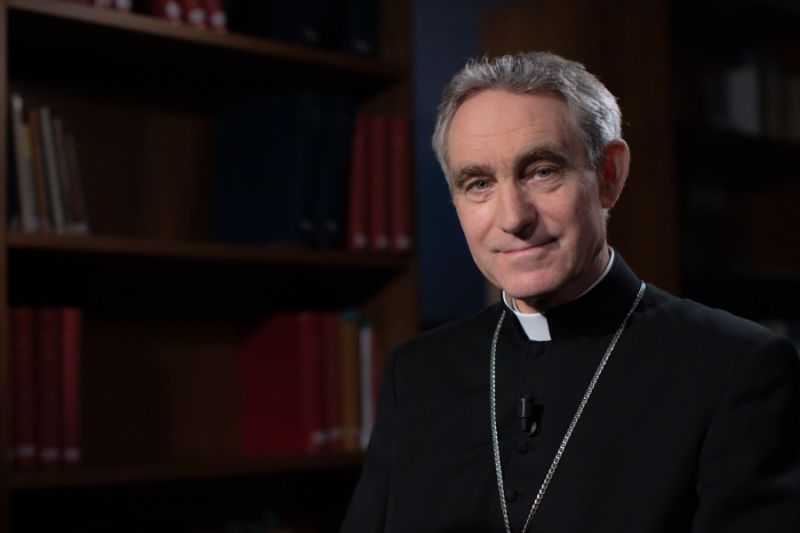

null / Daniel Ibáñez/CNA.

null / Daniel Ibáñez/CNA.

Rome Newsroom, Jan 11, 2023 / 12:48 pm (CNA).

In the latest book by Archbishop Georg Gänswein, for 20 years personal secretary to Pope Benedict XVI, there is much more than bitterness at having been made a “halved prefect” by Pope Francis.

Indeed, while the hype surrounding the publication has focused on that particular situation — the removal of Gänswein as prefect of the papal household — and has characterized Gänswein as willing to seek tension, almost to place one pontificate against the other, the book offers much more than that.

In fact, perhaps its most precious content is the excerpts from the homilies that Benedict XVI gave in the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery, where he spent the last years of his life.

Those homilies are probably the most innovative element of the book, which Gänswein wrote with journalist Saverio Gaeta. Titled “Nothing but the Truth: My Life Beside Benedict XVI,” the book comes out in Italian on Jan. 12, but CNA was able to preview it.

As long as his voice allowed him, Benedict XVI personally prepared the homilies, with notes written in pencil in a notebook that would then serve as a guideline for what he would say. They were simple, precise, straight-to-the-point homilies that the four Memores Domini (the consecrated laywomen of Communion and Liberation) who served as Benedict XVI’s family recorded and transcribed.

Only a few could listen to some of those homilies because Benedict XVI rarely received people, so the report of those homilies is an invaluable treasure.

What else can be found in the book? First, of course, there is Gänswein’s open anger and surprise at being abruptly relieved of his post as prefect of the papal household by Pope Francis, without any explanation.

Other previews spoke of Benedict XVI’s bitterness in learning about Traditionis custodes, Pope Francis’ apostolic letter with which he overturned the former pope’s decisions to expand the celebration of the ancient Mass.

However “juicy” these details may be for the media, they are certainly not the most novel element of the book.

Without diplomatic filters, using the straightforward language that those who know him are used to hearing, Gänswein outlines various interesting and partially unpublished situations. These include: the case of the book by Cardinal Robert Sarah, which named Benedict XVI as co-author; contacts with Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio before and after he became pope; the long letter that Benedict XVI wrote to Pope Francis to comment on his first interview granted to La Civiltà Cattolica in 2013, and a new details about how Benedict’s decision to renounce the pontificate came about.

The book offers insights to these stories and others through the eyes of a direct witness. It should be understood as a memorial, not an indictment. It provides a faithful account of situations and stories as Gänswein experienced them.

The resignation

In some cases, new facts are given and previously known accounts are presented in a different light. One example is Gänswein’s explanation for why Benedict XVI placed the pallium on the tomb of St. Celestine V, the pope who renounced his pontificate in 1294. His tomb is in L’Aquila, in central Italy, where Benedict had gone in 2009 to visit areas affected by an earthquake.

Benedict’s gesture has been interpreted as an indication of a willingness to resign that would occur several years later.

However, it was not like that, Gänswein reveals. He explains that Benedict XVI wanted to do an act of homage to his predecessor. So he placed a pallium, which Archbishop Piero Marini, at the time master of liturgical celebrations for Pope John Paul II, had sewn. This pallium fell uncomfortably on the shoulders of Benedict XVI, who thus took advantage of the opportunity to pay homage and donate it. The decision also tells much about how Benedict XVI dealt with the issues: He sought elegant solutions without offending anyone while trying to unite everyone.

However, the details of the decision to resign are more dramatic. Gänswein explains how Benedict XVI had already begun withdrawing into more profound prayer after his trip to Cuba and Mexico in 2012. There were indications that he was considering resignation, which triggered some questions asked by Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, then secretary of state. But such a decision was inconceivable.

When Benedict XVI reached the decision, there was no way to change his mind, Gänswein reports. Bertone and Gänswein only managed to convince him not to make the announcement during his annual Christmas greeting to the Curia on Dec. 21, 2012, but to postpone it a bit. If the announcement had been made on that day, and the pontificate had ended on Jan. 25, Christmas would not have been celebrated, Gänswein writes.

Benedict XVI

In Gänswein’s story, Benedict XVI emerges as an ironic man — learned, methodical, and brilliant — but above all as a man of faith. Naturally introverted, Benedict XVI withdrew into himself and silence when there were important issues. And he prayed. He prayed more intensely. He prayed hard. He did so moved by an unshakable faith and the need to live and understand the meaning of events.

As John Paul II was dying, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger became increasingly reflective. Finally, when it became clear that he was being thought of for the succession, he almost withdrew. But then, after prayer, after having matured the decisions, Ratzinger was a serene, convinced, and determined man.

Ratzinger was also loyal, close to his collaborators, careful not to harm any of his friends. Benedict XVI sought harmony — a fact that emerges clearly from Gänswein’s account.

The Sarah case

The search for harmony can also be seen in the Sarah case, or “Pasticciaccio Sarah,” as Gänswein defines it. The reference is to Cardinal Sarah’s book, “From the Depths of Our Hearts,” which also included an essay by Benedict XVI. The essay was dedicated to the question of priestly celibacy, and it was believed that it would come out after the publication of the postsynodal exhortation Querida Amazonia in February 2020.

However, it came out earlier, on Jan. 15, 2020, because Pope Francis had only approved the text on Dec. 27, 2019, creating the impression that the book was intended to influence the pope’s reflections on the Amazon Synod.

Such a motive wasn’t true, Gänswein writes. Nor was it true that Benedict XVI had been informed that he would appear as co-author.

Gänswein explains the situation, recalling that Sarah asked Benedict XVI to sign a press release to defend the operation. Gänswein was against it; Benedict XVI took time to think and then drew up a statement deferring the decision to his superiors. And Pope Francis let it be known that it was better not to publish.

At that point, tweets arrived from Sarah’s account, claiming that Benedict XVI had read and approved the drafts. There also was a dramatic confrontation between Gänswein and the cardinal in which the latter blamed Nicolas Diat, the journalist who had written several books with Sarah and who was described as the “director of the work.”

Gänswein’s account reveals much resentment over the situation. But it also includes a long letter that Benedict XVI himself sent to Pope Francis, published almost in its entirety, explaining his position and role in the affair and to clear the air of any possible idea of an opposition between Francis and the pope emeritus.

Benedict, La Civiltà Cattolica interview, and the Jesuits

Benedict XVI’s letter to Pope Francis is not the only unpublished work by the pope emeritus included in the book. Pope Francis spoke in 2013 to the Jesuit magazine La Civiltà Cattolica and sent the notebook used with the interview to Benedict XVI, asking him for comments. Benedict did so by writing a long letter to the pope, dated Sept. 27, 2013. In it, Benedict XVI insists on two aspects: that it is necessary to fight against the “concrete and practical denial of the living God” accomplished through abortion and euthanasia, and being aware of gender ideology, defined as manipulation.

But Benedict XVI and Francis had almost “touched” on other occasions. At the beginning of Benedict’s pontificate, some situations of the Society of Jesus were discussed, and even a commissioner was considered. Cardinal Bergoglio argued that there was no need for a commissioner, obtaining the promise that that provision would never take place.

Gänswein

Overall, in his book Gänswein is outspoken about critical situations. He does not shy away from admitting that he was wrong in some cases, but he also has no problem denouncing false reconstructions about the pope and his collaborators.

From the book’s narrative, all in the first person, emerges a private secretary still working for his superior. Every situation considered controversial or misjudged by the press is re-explained in great detail.

Gänswein looks at Benedict XVI almost like a father, with kindness for what seems to be naïveté and the admiration of one who knows that Benedict XVI is perfectly capable of carrying on his work because he knew, studied, and committed himself.

His role is to be “glass” — i.e., transparent, clean, and honest — but also a gatekeeper for those who want to get closer to the pope. This is what he has always done and tries to do in this book.

One could discuss at length whether or not it was prudent to publish the book right after the death of the pope emeritus. However, the message Gänswein wants to send is not that of controversy. Gänswein recounts his years with Benedict XVI, even removing a few pebbles from his shoe, but without entering into polemical tones with anyone.

The publication has likely done Gänswein more harm than good for now because it has allowed a campaign against him and, consequently, against the pontificate of Benedict XVI.

And yet, the pages written by the personal secretary of the late pope emeritus appear sincere, full of unpublished works and unknown stories. They are the pages of a faithful servant and of a man raised in the school of Benedict XVI; that is to say, accustomed to making God the center of everything.